Rebuilding after the Great Fire

After the Great Fire of London, the city was in disarray. Charles II pushed for evacuation of homeless refugees from the city, fearing a rebellion of workers who had lost family members and their jobs. Even before the fires had settled down, street violence broke out between Englishmen and the much-feared French and Dutch, whom the former blamed for having started the fire. Dozens of churches were burned to the ground, along with St. Paul’s, Guildhall, and The Royal Exchange.

And so, once civil unrest had died down and the dead and wounded were being treated, parliamentary attentions turned towards plans to rebuild. There were three key proposals made by three learned men: John Evelyn, a gardener and diarist; Robert Hooke, a polymath specialising in what we now call natural science, and Christopher Wren, also a scientific polymath with a flair for architecture. All three were highly esteemed academics who were in contact with, or were part of, the Royal Society.

None of these plans were accepted. London was rebuilt almost exactly as it had been before the fire, layout-wise, due to the legal difficulties of revoking tenures in order to build across what was once someone’s home. St Paul’s was famously re-designed by Wren, but his layout plans weren’t adopted.

But what if one of these plans had been accepted? London would surely be a very different city from the one it is today.

Under John Evelyn, London would have become a beautiful garden. He presented this plan directly to King Charles, describing how the gardens would be interspersed with piazzas, as well as being completely free of pollution. London’s walls, declared Evelyn, would keep pollutant trades out of the city completely. In a modern context, the biggest difference would be the lack of motorised road vehicles. No cars, no buses, no motorcycles. It really is hard to imagine.

In addition, the Port of London would be moved to the South Bank, while streets would become much wider (as is the case in many modern European countries). St. Paul’s would be the centrepiece of the city under Evelyn’s plans; that much, to an extent, is so.

Robert Hooke had a much less idyllic vision in mind, but by no means an uninspired one. An expert in geometry, he wanted London to become a perfectly-aligned grid of exact squares. This would have required a complete overhaul of the damaged area, thereby erasing the previous streets. Such a vision was and is very practical had Hooke been designing a city from scratch, but for a rebuilding project, it simply required too much manual and legal work. The effectiveness of the grid system can be traced throughout history; the Romans used it for land measurement, and it can still be found in modern cities like New York and Washington D.C.

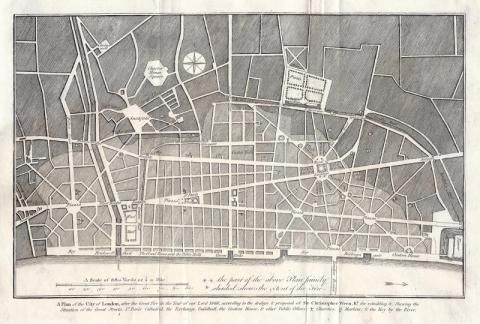

Like John Evelyn, Christopher Wren wanted St. Paul’s to be London’s centrepiece after the rebuilding, but his designs had a lot more in common with Hooke’s. The King’s Surveyor of Works, he hoped to win royal assent by pushing for a largely geometric layout, but with angular roads cutting through the grid system. Much like Roman roads, these were straight and wide, going on for great distances and providing easy access to outer London areas. Most drastically, he sought to clear and then reposition London Bridge. Even though his redesign plans were refused, however, he and Hooke ended up heavily assisting the rebuilding process.

Of course, even if one of these three plans had been implemented, it may have later been superseded by another redesign in the ensuing 400-odd years, but the effect it could have had would still be seen in London today. London would be a completely different city. But even in 2017, it still largely retains its pre-fire layout, and that’s a source of some wonder.

The above photo is a map, drawn up shortly after the fire, of Christopher Wren’s London